This article was published in Business Times on 20 Jan 2007. I thought it was an interesting insight into the motivations and aspirations of a world-reknown architect whose first building was built only when he was 54! It inspired me in certain ways, to push on in what I believe architecture is to me, perhaps it might bring some encouragement to you too!

Daniel Libeskind tells PARVATHI NAYAR why he regards architecture as 'the mother of the arts'

WHEN Berlin's Jewish Museum finally opened in 2001, its startling zigzag form, zinc exteriors, and dramatic interplay of solids and voids attracted vast public interest and generous critical plaudits. There were 200,000 visitors in the first two months alone. It was a great success that made the architect's name, but the really interesting details are that it was the architect's first building and that he was already 54 years old.

'He was a late bloomer,' says Nina Libeskind about her superstar architect husband.

Architecture isn't a profession of quick returns. 'An architect is a marathon runner not a sprinter,' chuckles Daniel Libeskind, who was in town to launch the exhibition Between, Beside, Beyond at the Singapore Art Museum which features 16 of his key works, and to launch the condo he is building for Keppel Land, called Reflections At Keppel Bay.

'Many run out of breath and drop out,' he says, continuing the marathon metaphor, 'but those who know how to time themselves can reach a goal - which is often very elusive. Architectural projects of grand complexity take a long time. Also, I have worked on a lot of projects that are particularly difficult - not necessarily architecturally, but socially or politically, like the Jewish Museum or Ground Zero.'

If the former laid the foundation of his fame, the latter catapulted him to stratospheric levels. When Studio Daniel Libeskind was selected as the design team of the new World Trade Center site in 2003, the architect became a household name in the West.

It has been a pretty eventful ride since.

Memory Foundations - as the World Trade Center master plans are called - have attracted more than its share of controversy about Libeskind suing the site's developer, Larry Silverstein; differences of opinion between Libeskind and David Childs, the architect of the site's proposed centrepiece, the Freedom Tower; the seemingly endless delays in starting construction; and, most critically, the final plan being very different from that conceived by Libeskind.

Memory Foundations - as the World Trade Center master plans are called - have attracted more than its share of controversy about Libeskind suing the site's developer, Larry Silverstein; differences of opinion between Libeskind and David Childs, the architect of the site's proposed centrepiece, the Freedom Tower; the seemingly endless delays in starting construction; and, most critically, the final plan being very different from that conceived by Libeskind.

'Don't listen to architecture critics,' says Libeskind affably, noting that what is being built now looks remarkably like his original master plan. 'The first beams for the Freedom Tower were placed in December, the slurry wall is being readied, new streets are being created, the flanking office buildings have been presented exactly as I had them in my composition. I'm really excited it is actually under construction. I see it from my office window every day, and it's going to be something inspiring. What emerges there is not simply another piece of real estate but something about the spirit of New York that rises to the sky in an optimistic way.'

As to Freedom Tower itself, 'I'm not the architect of that tower but it follows very closely my ideas. It is standing exactly where I wanted it to be, and is 1,776 feet, which will symbolise the year of American independence. It has what I required, platforms at the original World Trade Center height, so people can see what it was like then, as well as a torch-like element at its apogee.'

As to Freedom Tower itself, 'I'm not the architect of that tower but it follows very closely my ideas. It is standing exactly where I wanted it to be, and is 1,776 feet, which will symbolise the year of American independence. It has what I required, platforms at the original World Trade Center height, so people can see what it was like then, as well as a torch-like element at its apogee.'

The torch at the top means that how the Freedom Tower will look from the water will have resonances with the Statue of Liberty - and this links back in time to Libeskind's first viewing of the torch-bearing lady when he was arriving by boat as a young immigrant to the US.

The torch at the top means that how the Freedom Tower will look from the water will have resonances with the Statue of Liberty - and this links back in time to Libeskind's first viewing of the torch-bearing lady when he was arriving by boat as a young immigrant to the US.

Born in Poland in 1946 as the son of Holocaust survivors, Libeskind emigrated to the US when he was 13 years old, and attended the Bronx High School of Science. Architecture was not the arena of Libeskind's first display of excellence; he had been a child prodigy and virtuoso accordion player, and studied music in Israel on the America-Israel Cultural Foundation Scholarship. At the urging of Isaac Stern, he switched from the accordion to the piano. He continued to play the piano in the Bronx, and also pursued mathematics for a while, but in the 1970s traded it all in for architecture.

Even before he built his first building, when he was studying, teaching and writing, 'I always thought I was doing architecture. Architecture is bigger than just building a building. When I started on the path I didn't have a goal, but it was my own path; I started with drawings, investigations of history and archaeology - and along the path also found opportunities to build buildings and design cities.'

Libeskind was known within the architectural circles for his multidisciplinary approach, so it was no surprise that when he started to build, the buildings ranged from museums to universities, shopping centres and homes, or that he has designed opera sets and has set up an object design studio. Currently, Libeskind has ambitious ongoing projects round the world such as the Fiera Milano in Italy and Hong Kong's Creative Media Centre.

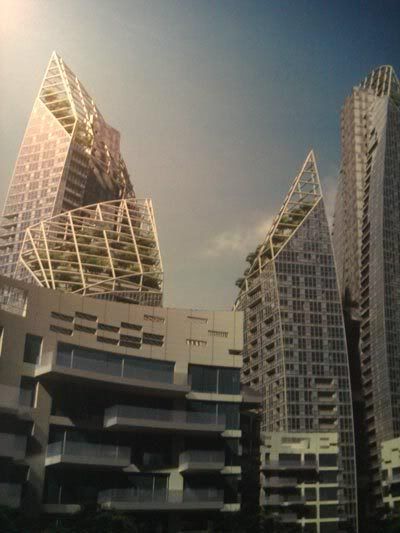

Or, closer to home, Reflections At Keppel Bay, which Libeskind likens to a musical composition. Situated on 84,000 sq m of land, the residential complex will consist of six dramatically curved skyscrapers with skybridges, and 11 blocks of low-rise villas.

Or, closer to home, Reflections At Keppel Bay, which Libeskind likens to a musical composition. Situated on 84,000 sq m of land, the residential complex will consist of six dramatically curved skyscrapers with skybridges, and 11 blocks of low-rise villas.

The Keppel development may be Libeskind's first residential site in Asia, but the first residential project he ever undertook was part of his gigantic Westside project for leisure and shopping, currently being built in Brunnen, Switzerland. The 60-year-old architect says: 'It's a huge multi-dimensional, mixed use development that radically reinvents the concepts of entertainment and shopping in 21st century life. I suggested that homes for the elderly should be part of this complex: Where else is better for the elderly than where the young people are?'

But if you think building homes is low down on his list of priorities: 'There's nothing more challenging than a residential building. It's not about designing a zappy space that works for partygoers but a place where people spend their lives. Every element of the project has to have a spirit of care. It's not disposable. It's no coincidence that the dwelling - not the museum or city hall - is the source of architecture. We judge cities not just by their great monumental spaces, but how people live in them.'

'What I do in Singapore is part of that belief.'

His own home is 'very modest, a loft in Tribeca, New York. It is very simple, modern, contemporary, a bare space that is also pleasant. We don't have much clutter in the house. I'm not nostalgic about keeping things, but it has the things I love: Books, pieces of furniture like a Mies lounge, and the little things I was given by my kids like a good-luck Buddha they bought in Chinatown. We still have a teenager - my daughter Rachel - living at home; sometimes when Rachel's friends visit they say it is like a movie set, does anyone actually live here?'

More on his Tribeca apartment: 'Some would say it's a very cool place with its grey Italian stone floor and soft white walls and lots of black, grey and red; I love red. I took out all the old windows and replaced it with very, very large windows that have hardly any mullions. Because it's also about how it is located vis-a vis New York; a great building is not just for itself but how the inside is related to the outside.'

Recently Libeskind was appointed by the State Department as the first Ambassador of Culture for Architecture. One tour of duty took him to India last year. He went with his two sons, travelling all over Northern India. It was his first trip there, but 'I'm a great fan of Indian philosophy and literature so I felt I had 'visited' India before. I spoke to large groups of students about architecture and about what they are doing. It was a very moving experience.'

So architecture has brought him all sorts of rewards; still, does he miss trading music for architecture?

As it turns out, music is an integral part of his life in many ways. For starters, he listens to music a lot. His tastes in music are 'eclectic, from classical to ethnic', and the presence of his teenage daughter means that it's not just Bach that plays in the Libeskind household. He chuckles: 'Yes sometimes I have to listen to rap and navigate through commercial music, to find that there are some great things there too, a great voice, for example.'

What's more, he is currently relooking the architecture of the piano. 'An old German family-owned company came to me and asked me to redesign the grand piano, and I accepted. They - and I - saw no reason why the piano should have this 17th century form. The project started a few years ago, and is now under way. It will take a bit of time because it's not just about redesigning the casing, but how a piano operates. I wanted to design a piano that not just a contemporary player would enjoy, but the great pianists like Glenn Gould or Horowitz would want to play.'

'I don't perform any more, it's hard to be a hobby player when you were once a virtuoso.'

Libeskind also sees parallels between architecture, drawing and music; all are 'acoustical'. An architectural drawing has to be conducted, resonate in a certain way and be a successful performance. Before you press the keys of a piano there is a certain impulse, which is no different from the pressure that directs the hand holding a pencil to draw.

'I have always done drawing, there is no 'why', no explanation for such a thing. There is a magic in drawing. It is so deep. It is one of the first artistic activities that human beings ever did, it is the source of writing, construction, architecture.

'The drawings that create a building are not really technical drawings but the artistic hand-drawn conception of what it might be - which later has to be elaborated into a technical drawing. I personally don't use the computer. When I start an architectural project, I draw. Out of the drawing comes an understanding and a relationship to the landscape. The art of architecture is drawing. The building then captures the spirit of the drawing, it isn't just an imitation of the drawing.'

He explains, narrating a lovely incident about another ongoing project, The Crystal, which is the extension to the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada. He did an emotive sketch for The Crystal on the material of choice for all spontaneous, inventive ideas: a napkin. However he put it away, thinking it was an impossible task to actually make a building like his sketch. 'But now when I look at the building - that will open in the summer - it's amazing just how much it does look like that first intuitive sketch.'

Initial emotive sketch of The Crystal

Initial emotive sketch of The Crystal

Rendering of actual design

Rendering of actual design

Many architectural projects in today's world - including designs created for unsuccessful bids for architectural competitions - do not get built. Is Libeskind disappointed over his involvement, say, with the unsuccessful bid by Harrah's and Keppel for the integrated resorts project in Singapore, or about the as-yet-unbuilt extension to the Victoria & Albert Museum in London?

He replies: 'I'm not an architect who wants quantities. I never think that we have 'lost' any projects, I don't see it that way. I continue to evoke them, they continue to be alive and part of my work. What I invest in architecture is similar to what I invest into human relationships; if you want something back in return then, no, you don't actually have a relationship.'

In a world shaped by influences that range from technology to terrorism, 'architecture brings stability, not in a rigid form but in its cultural human form. It is part of what is sustainable for human life, it sets the stage for creativity, imagination - and the everyday. Architecture is the horizon we see, the ground we walk on, our orientation of the past to the future. There is a good reason why architecture is called 'the mother of the arts'.'For architecture is not about itself, it's about everything else, it's about life. Architecture is an artwork,handcrafted; somebody makes these things by hand. Everything matters, from a doorknob to a bathroom tile, from the masterplan to the silhouette; there is nothing which is unimportant.

In that sense Mies van der Rohe was wrong, God is not in the details, God is everywhere.'

Copyright © 2005 Singapore Press Holdings Ltd. All rights reserved.

Little India back alley

Little India back alley